Indigenous-authored novels: 5 great contemporary reads for young adults

The Toronto District School Board recently pledged to replace Grade 11 English courses in all 110 of its secondary schools with the now-mandatory First Voices course.

First Voices is a Grade 11 English course that replaces works by authors like Shakespeare and Fitzgerald with texts authored by Indigenous writers like Cherie Dimaline and Richard Wagamese.

Since Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its final report in 2015, schools across the country have been advancing curricula to align with calls for reconciliation education.

Over the summer, our Indigenous literatures lab, led by Haudenosaunee scholar Jennifer Brant at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, examined contemporary Indigenous-authored young adult texts that are well-suited for the First Voices course.

Importance of Indigenous perspectives

With the replacement of long-read literature comes the task of selecting texts that centre Indigenous resurgence and what Indigenous literary scholar Gerald Vizenor refers to as survivance. Survivance encompasses an active sense of presence, merging both survival and resistance.

We hope to see the stories in classrooms across the country that centre Indigenous community narratives from the voices of Indigenous Peoples.

Such stories may not always be happy or gentle, but they tell truths of Indigenous presence and visions for empowered futures.

Upholding responsibilities

As Cherokee author and scholar Daniel Heath Justice writes, good stories are needed that give “shape, substance and purpose” to Indigenous Peoples’ existences and shed light on how to uphold responsibilities to one another and to creation.

These stand in contrast to stories Justice discusses as “bad medicine,” stories often imposed from the outside, from the perspective of the colonizer. These stories are noxious and can poison both the speaker and the listener as they often perpetuate deficiency narratives about Indigenous Peoples.

This analysis speaks to the definitive need for Indigenous-authored texts in the First Voices course, and also for educators to pay attention to how these books are taught.

As interdisciplinary researcher Jennifer Hardwick suggests, “decolonizing narratives can be misread as colonial if readers do not have the knowledge-base to engage with them … It is not enough to introduce Canadians to decolonizing narratives; decolonization needs to begin with a process of unlearning and re-learning.”

Engaging with books

Métis professor Aubrey Jean Hanson proposes a framework of resurgence and explains that this process relies on the willingness of non-Indigenous students and staff to engage substantially with Indigenous literary texts.

We encourage educators to take a strength-based perspective when discussing Indigenous literature, and also to take an anti-racist approach. Anti-racist approaches acknowledge varied experiences of racism, and would help students think critically about their own lives in relationship to these books.

Books featured here are highly acclaimed, and show narratives of Indigenous resurgence. All except one are recently published.

The Indigenous literatures lab will continue to review new literary material to support educators as they learn to engage with Indigenous-authored texts in ethical and relational ways.

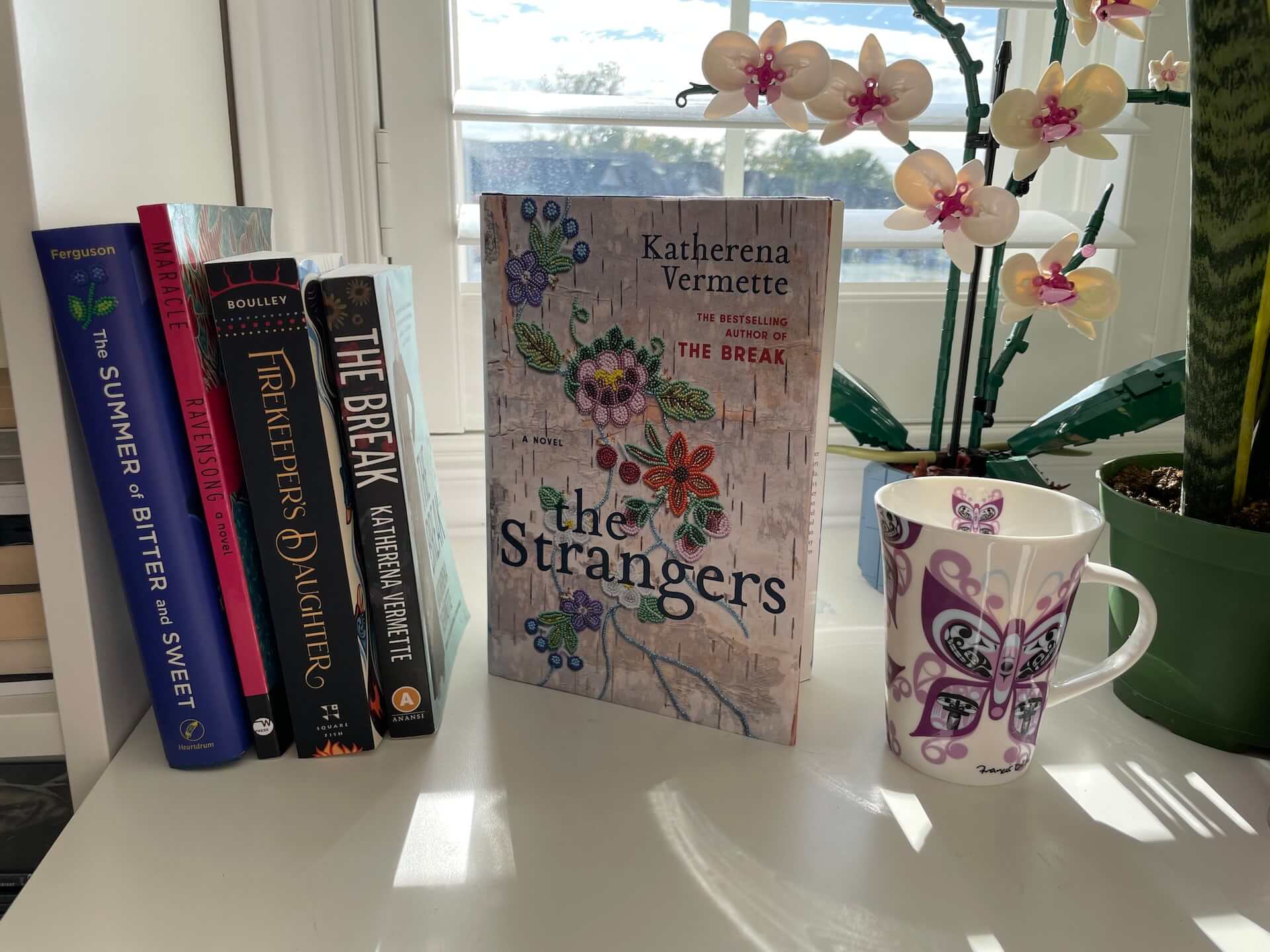

1) The Break (2016)

The Break, Katherena Vermette’s debut novel, is the winner of the Amazon.ca First Novel Award, the Carol Shields Winnipeg Book Award, and was a finalist for other prestigious awards.

It is a story about a Métis-Anishinaabe teen and her family who are drastically impacted by a violent crime in Winnipeg. As investigations uncover many unknowns, readers get meaningful insights into the realities of various characters whose lives are intricately woven together.

The book delves into themes of family, strength, womanhood, love, and the power of generational resiliency. This novel provides a snapshot of the experiences faced regularly by Indigenous women and girls in Canada — and how systems (like policing and justice systems) often fail to protect them. Vermette’s rich and complex storytelling enthralls the reader, making this book a must-read.

2) The Strangers (2021)

The Strangers, by Katherena Vermette, is a No. 1 National Bestseller, and winner of numerous awards, including the Atwood Gibson Writers’ Trust Prize for Fiction.

Vermette is a Red River Métis (Michif) author from Treaty 1 territory. The Strangers is a sequel to The Break, but can also be read as a stand-alone novel. It explores the ways government systems (child welfare, health care, education, and social services) are failing Indigenous Peoples, while at the same time expecting Indigenous Peoples to fail.

Vermette powerfully weaves the stories of four strong women to tell an inter-generational story about rage, trauma, memory, hope, and the power of family as an anchor to home.

3) The Summer of Bitter and Sweet (2022)

Jen Ferguson’s debut novel follows the narrative of a Métis girl, Lou, as she works at her family’s ice cream shop the summer before she starts university. Set in the Canadian Prairies, readers witness the complexities of growing up as a mixed-race teen in a part of the world where anti-Indigenous racism is prevalent.

Lou is forced to navigate this reality all while overcoming intergenerational trauma, mending broken relationships and discovering her own sexuality. Lou often relies on anger and secrets as a means of survival, but by exploring her identity, gaining a better understanding of her family’s strengths and their determination, she comes to understand what it means to be proud of who she is, where she comes from and the opportunities that await.

It is no surprise this book won the 2022 Governor General’s Literary Award for Young People’s Literature!

4) Firekeeper’s Daughter (2021)

Firekeeper’s Daughter by Angeline Boulley is a New York Times bestseller, winner of the Michael L. Printz Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature and other significant honours.

This action-packed novel takes readers on a thrilling journey of an FBI investigation. The protagonist, Daunis, must use knowledge of her Ojibwe culture and identity to solve a mystery and murder in her town, while navigating high school, love and friendship, family and kinship, and hockey.

Firekeeper’s Daughter is a great introduction to Indigenous ways of knowing, while addressing negative narratives that exist. This novel will keep readers on their toes.

5) Ravensong (1993)

Ravensong by Sto:lo writer and award-winning author Lee Maracle is set in a 1950s Pacific northwest coast community that borders a settler community referred to as white town. The protagonist, 17-year-old Stacey, walks into white town daily to attend high school as one of the only Indigenous students in a world defined by significantly different rules and roles than the ones she knows.

It is a coming-of-age story. The book calls upon readers to see the world through the eyes of Stacey, who witnesses the injustices faced by Indigenous communities — along with the dehumanization of women in white town whose world is governed by a patriarchal worldview.

This story reflects on racialized, sexualized, and gender-based violence and how the power and beauty of Indigenous matrilineal laws can provide contemporary solutions to the many ills we face. Maracle recalls matrilineal traditions as a path for imagining a future in which we all thrive.

Maracle followed Ravensong with Celia’s Song, a finalist in the 2020 Neustadt International Prize for Literature.![]()

Jennifer Brant is Assistant Professor in Curriculum, Teaching and Learning, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto; Erenna Morrison is a PhD Candidate in Curriculum and Pedagogy, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto; Gayatri Thakor is a PhD Student in Curriculum and Pedagogy, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto; and Meagan Hamilton is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Curriculum, Teaching and Learning, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.