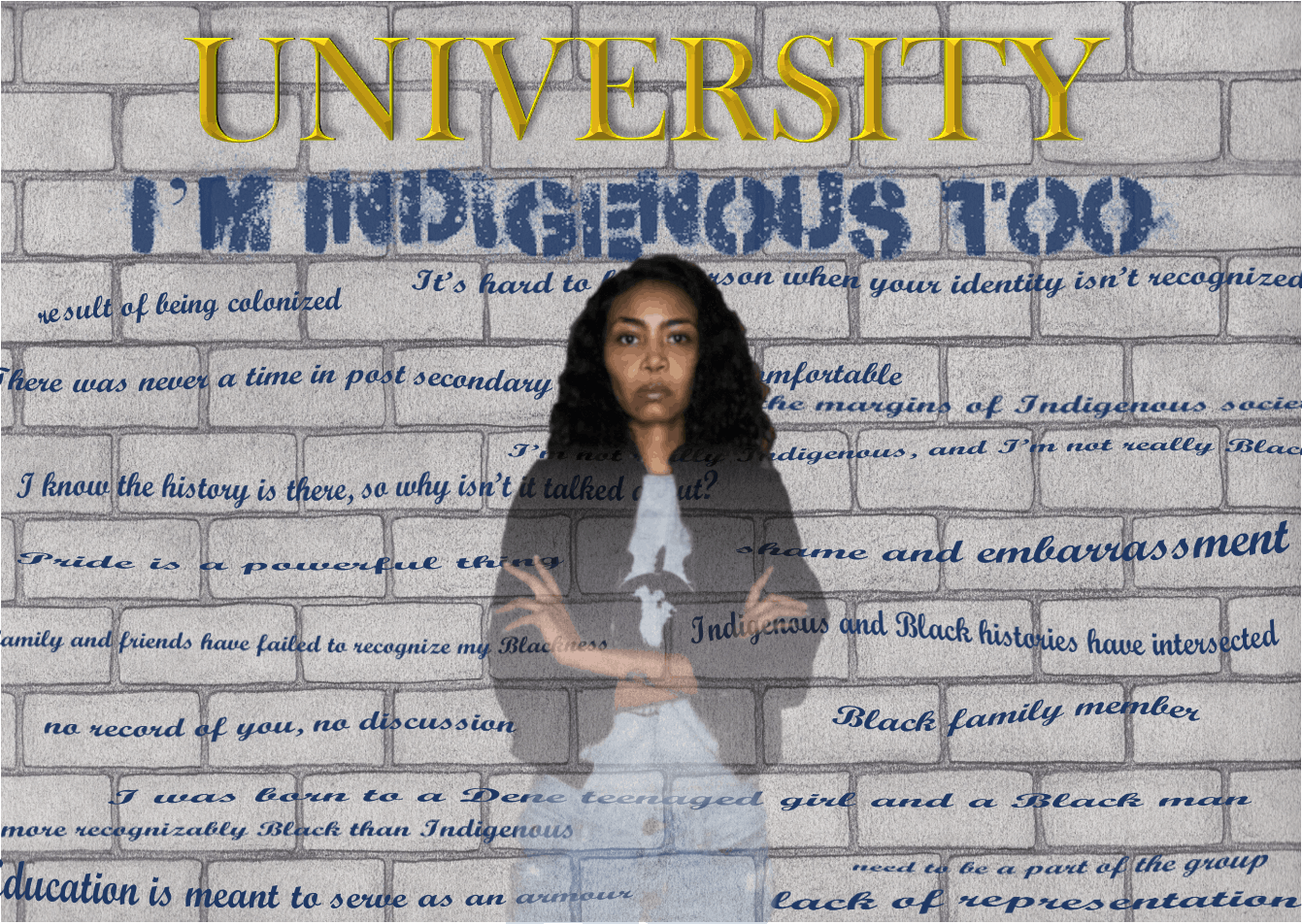

Writing Myself Into Existence: An Essay on the Erasure of Black Indigenous Identity in Canadian Education

I remember hearing somewhere that “no one wants to be Black.”

Thinking about that sentiment brings back a memory of my childhood, being pressured to put my arm next to the arm of my dark-skinned Indigenous friend. I remember desperately hoping that my arm wasn’t the darker one. It was, and when I saw that I felt shame and embarrassment.

More than 20 years later and I’m still struggling with the fact that the shade of my skin provokes anti-Black racism within my peers that keeps me in the margins of Indigenous society.

Layers of Insecurity

In 1983, I was born in Yellowknife, N.W.T, to an 18-year-old Dene teenaged girl and a Black man who was never present and never spoken about. My mother gave me up for adoption at birth to her dad and his second wife, who was an Anishinaabe woman from Couchiching First Nation. At the time, they lived in a township just outside of Fort Frances, ON. They separated when I was three-years-old and a year later my mom, brother, sister (children from previous relationships), and I moved to Thunder Bay, where I have lived ever since.

Growing up I never quite fit in, for many reasons. I look more recognizably Black than Indigenous in a city with virtually no Black people, in a family with no other Black people, in a house where I wasn’t biologically related to any of my family members who, along with my peers, were from a different Indigenous nation than I am. All these factors resulted in feelings of insecurity in my Indigenous identity.

I was thirty-years-old when I decided to go to university. I took a double major in Philosophy and Psychology at Lakehead but I couldn’t relate to my classmates (who were made up of mostly younger white students) or the content, which was based on a Western view of the world. I ended up dropping out two years later and went to Confederation College to take Aboriginal Community Advocacy (ACA). The ACA program fostered an awakening that I’m still experiencing: I learned about colonization, white supremacy, how Indigenous peoples have been victimized but how we have persevered.

The ACA program taught me that many Indigenous families’ traumatic circumstances were the direct result of being colonized. After learning all this, I was inspired to look into my family history. I learned that prior to contact with Euro-Canadian settlers, my family members were fiercely independent, strong, and intelligent. They thrived in the harshest weather conditions. In fact, when Euro-Canadians began to settle in the North they depended on my family members as well as other Dene people to survive. This discovery changed how I viewed myself and my bloodline. As much as it pains me now to admit it, my younger self believed that I was an inferior person who came from an inferior family. After learning that the purpose of colonization is to take over every part of Indigenous peoples’ bodies, minds, and spirits and displace them from their land, and how Indigenous peoples have continuously resisted this crushing reality, I felt pride for the first time in a long time in my Indigenous heritage.

Pride is a powerful thing. Pride gives you confidence, self worth, and motivation to keep moving forward even when it’s hard.

Still, feelings of insecurity remained. As much as I felt pride in my Indigenous heritage, I still struggled to know where I fit. Many of the classes I took in the ACA program and later at Lakehead University’s Indigenous Learning program covered Indigenous identity, including Métis experiences, and sometimes Black oppression was discussed as a comparison to Indigenous oppression. We looked at how white supremacy works to oppress both groups, for instance, but the relationship between the two groups was never mentioned, nor was the possibility that there could also be a Black-Indigenous mixed-race identity. It was frustrating to be in a program that focused so much on Indigenous identity but when it came to my Indigenous identity I was left to piece together the history on my own.

There was never a time in post secondary where I felt comfortable enough to express my feelings about this lack of representation. I’m not sure of the exact reason why. It could have been my uncertainty. Moments like having to compare the colour of my arm to the colour of my friend’s arm had made me feel uncertain of who I was as an Indigenous person. Another reason could’ve been the trauma of being shut down so many times when I’ve tried to express myself in the past. Or maybe it was the continuous need to be a part of the group and not wanting to rock the boat with my feelings of otherness within that group. Whatever the reason, I just didn’t feel safe enough to share my point of view.

Benefits of a Black Indigenous Curriculum

If Afro-Indigenous perspectives were incorporated into Indigenous curriculum it would not only fight against the erasure of Indigenous and Black history in Canada but also educate my classmates and teachers about the scope of Indigenous identity and impacts of colonization.

There is a story that sticks with me during my time in school; an Indigenous friend had told the class about her great grandmother who had been enslaved but runaway and settled on her reserve. She was called a liar because others from the same community had never heard of any Black people in the community; it simply seems impossible. I spoke to the instructor later and they encouraged me to research this link. But I shouldn’t have to do the research on my own time. If Black-Indigenous identity was already incorporated into the curriculum then it wouldn’t be so unbelievable when an Indigenous student reveals their connection to Blackness.

I know the Indigenous Black connection is true.

Many Indigenous people have told me they have a Black family member or ancestor. I even heard another story of a Black man who had escaped slavery and taken refuge in my Grandmother’s home community before leaving to make his way to England.

I know the history is there, so why isn’t it talked about in Canadian and Indigenous literature, and in the classroom, on reserve and in provincial schools? Why isn’t it even discussed in colleges and universities? Why isn’t it common knowledge that Indigenous and Black histories have intersected and intertwined throughout the history of colonization in the Americas?

Not only is this rich and critically important history necessary for an understanding of how we’ve all travelled through colonization together, being included in the curriculum could also alter how educators and students approach inquiries of racial identity in others.

Throughout my education I was asked about my race by my peers, and although they accepted my answer, their queries triggered those familiar feelings of self-consciousness.

Education is meant to serve as an armour that you wear out into the world and it protects you, but not seeing my experiences in the curriculum has left me feeling half armoured.

Decolonization (But for Black Indigenous People, too)

It’s hard to be a person when your identity isn’t recognized; when there is no record of you, no discussion. How are you supposed to come to an identity resolution when your identity is invisible? Having a dual racial identity feels like I’m constantly in a state of limbo, like I’m not really Indigenous, and I’m not really Black.

I’ve voiced my feelings about this many times in my communities but I’ve often been met with reactions of indifference or dismissal. Both my visibly Indigenous and white-passing Indigenous family and friends have failed to recognize my Blackness and how it alters the way I move through the world. I’ve been told that my experience is the same as theirs. They say Indigenous-looking people experience racism just like Black-looking Indigenous people or that white-passing Indigenous people experience feelings of exclusion from Indigenous communities just like Afro-Indigenous people. I don’t think these comparisons are true.

For me, the truth is that racial hierarchies affect everyone whether they realize it or not. We exist in a society where whiteness is the pinnacle and Blackness is in the gutter, and everyone in between organizes themselves in relation to that standard.

When we talk about decolonization or liberation, this reality is often ignored. But how are the oppressed supposed to free themselves if they can’t see their complicity in the oppression of others?

This is a fundamental question educators need to ask themselves in post secondary institutions. The Indigenous faculty members, students, and of course the non-Indigenous people, too. Overlooking non-European mixed-race Indigenous experiences and histories in the curriculum works to keep the colonial hierarchies in place and prevents us from being able to truly decolonize.

Etanda Arden is an Afro-Indigenous woman who is a long-time resident of Thunder Bay, Ontario. She is near completion of the Indigenous Learning HBA program at Lakehead University and has hopes of becoming a professional writer. Etanda would like to use writing to create space for the perspectives of disenfranchised groups.

This blog was originally published by Yellowhead Institute on January 28, 2021, and is republished with permission from the author and Yellowhead Institute.

Image by Etanda Arden.

Etanda Arden